Headlines about trade wars between the U.S. and other nations have been moving global financial markets this year.

In spite of talks toward free-trade agreements in other regions, trade frictions between the U.S. and China, the two largest economies in the world, have intensified recently. The increased frictions follow several rounds of cooperation, negotiation, retaliation, and escalation. So far, there has been limited progress on cooperation and negotiation. Instead, there has been another round of tit-for-tat tariffs on imports. The U.S. also has announced an additional tariff list that could take effect in the fall, if implemented. This has pushed us much closer to a trade war.

In disputes such as these, there are two final scenarios: win-win and lose-lose. Given the greater temptation not to cooperate, an ending in which both players lose is quite likely. Hence, it is understandable that the markets are highly concerned about an eventual trade war, especially since the risk of miscalculation and miscommunication between the U.S. and China is quite high, given numerous social, political, and cultural differences between the two countries.

The silver lining is that this is not a one-shot game. The U.S. and China could go for several rounds before they eventually settle into a more stable relationship, for better or worse. It is true that neither side is willing to let the other win easily and that each is still trying to test the other's limit at this moment. However, when the pain of the trade war becomes unbearable, the players may decide to back off, get back to the negotiation table, and restart. For the U.S., it may take a sharp decline in the financial markets and a significant deterioration in the labor market. For China, it could be the risk of a sharp deceleration of economic growth to below 6.3%, the pace necessary to achieve China's goal of doubling its 2010 GDP by 2020. Obviously, we are not there yet.

Higher chance of ending up with the lose-lose scenario

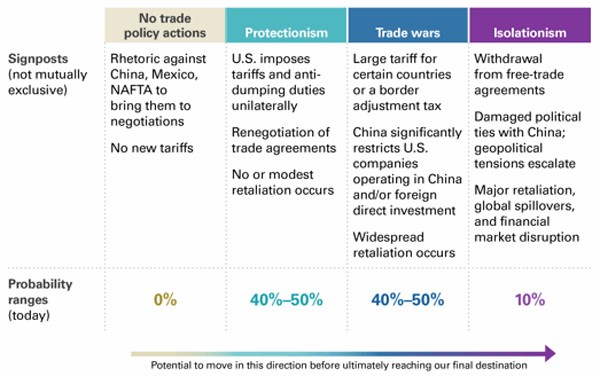

As the U.S. midterm elections approach, there is a decent chance of further escalation in the near term. Hence, we have revised the chance of a “trade wars” scenario from 30%–40% in May to 40%–50%. A trade war would lower growth in both the U.S. and China. The direct impact on growth in both countries would be manageable. Obviously, both are major players in the global economy; combined, they produce 38% of the world's GDP. However, their international trade, as large as it is, represents only 1.8% of total world trade and about 2% of their combined GDP. China's exports to the U.S. represent about 4% of Chinese GDP and U.S. exports to China represent about 1% of U.S. GDP.

Nonetheless, the indirect impact could be felt through the effect on the labor market and consumption, or via the effect on financial markets and business confidence.

This won't lead to a hard landing, but it does pose some downside risk to China's 6.5% growth target this year. In fact, Chinese policymakers have paused their deleveraging campaign and started to ease monetary and fiscal stimulus to cushion the potential negative impact from trade frictions. Our U.S. economists believe that in this scenario, the U.S. economy could face a modest reduction of 10–15 basis points given China's retaliation. In fact, since the second-order effects would be the more important negative driver, the U.S. administration will keep a close eye on financial market developments.

There will be a spillover effect on the rest of the world, too. From a value-added perspective, more than one-third of the goods exported from China are actually made somewhere else. This is particularly true for China's electronic and machinery exports, which have been the target products in the U.S. government's investigation into China's trade practices. For every dollar of goods that China is exporting, 20 cents comes from Asia and 7 cents from Europe. Certain Asian markets would be particularly vulnerable, such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, given how integrated they are into the regional supply chain. Nonetheless, as long as the trade war is strictly limited to tariffs and protectionist measures, the global economy may not collapse into a deeper recession.

We see a 10% chance of ultimate “isolationism,” which would involve damaged diplomatic ties between China and the U.S. on multiple fronts—economic, political, and cultural. If major retaliatory measures are involved—such as a broad-based sanction against China and China's dumping U.S. Treasury bills in return—it could result in significant financial market disruption and eventually a global recession. Luckily, the chance is very low in our view since the outcome would be extremely negative for both China and the U.S., as well as for the rest of the world.

Not yet at the point of no return

Despite a higher chance of a trade war, there is still hope for eventual peace. Both countries understand that a trade war would be a lose-lose situation. As such, we continue to believe there is room for negotiation, especially when the pain becomes unbearable. We assign a 40%–50% chance to a “protectionist” scenario, with modest implementation of trade tariffs/retaliation and an ultimate negotiation on a comprehensive trade and investment agreement between China and the U.S. Even so, the path to that eventual deal is likely to be bumpy. While this scenario will have only a marginal impact on the global economy and inflation, it will translate into volatility in the market.

Trade frictions to get worse before getting better

Select U.S. tariffs likely to be used to gain leverage in future trade negotiations.

Source: Vanguard Investment Strategy Group as of July 2018

U.S. and China frictions over the long haul

Disagreements on bilateral trade represent only the first of two conflicts between China and the U.S. The other conflict is over longer-term issues and will be much more strategic and prolonged. It will focus on issues fundamental to the structure of the Chinese economy. The U.S. is pressuring China to live up to its promise to the World Trade Organization by further opening markets and pushing forward market-oriented reforms. Hence, although a comprehensive trade and investment agreement could be reached eventually, the bumpy path of negotiation on other issues will continue.

On this front, China has shown willingness to cooperate as this would ultimately benefit its long-term development through more efficient capital allocation. That in turn will eventually lead to higher productivity and growth potential. Indeed, President Xi announced at April's Boao Forum that China is planning to further open the domestic financial market, relax the foreign ownership limit in the auto and financial industries, enhance the investment environment, strengthen protection of intellectual property rights, and ensure a level playing field. However, the pace and scope of any such opening and reforms are at the core of the second conflict, especially regarding government subsidies to high-tech industries and state-owned enterprises.

What should investors do?

Along with the long and bump path of negotiation between the U.S. and China, volatility in global financial markets is likely to persist. Despite the up and downs, we advise investors, first, to maintain a diversified portfolio given the heightened uncertainties in the current environment and, second, stick to their long-term investment portfolio. That should give investors a better chance to weather the short-term volatilities and achieve long-term investment success.

By Qian Wang, PhD

Managing Director and Chief Economist, Asia-Pacific

14 August 2018

vanguardinvestments.com.au